Buck Converter Design

Buck Converter Design

Before reading this section, please read the introduction.

All the circuits in this tutorial can be simulated in LTspice®. If you are new to LTspice, please have a look at my LTspice Tutorial

In order to efficiently reduce a high voltage to a lower voltage, a buck dc/dc converter is needed.

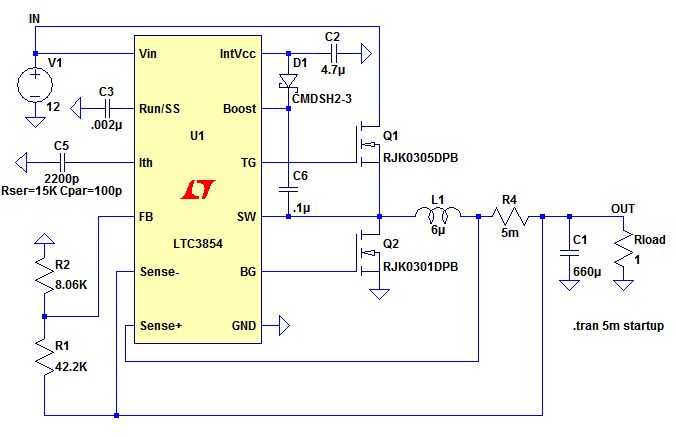

Consider the circuit of Figure 1

Figure 1

The top MOSFET switches on creating a short circuit between the input voltage (IN) and the left hand side of the inductor, L1. The inductor current ramps up according to the equation

where V is the voltage across the inductor, L is the inductance value and di/dt is the change in current with time through the inductor. Thus with a fixed input voltage and a fixed output voltage, there is a fixed voltage across the inductor thus the change in current with time is constant (i.e. a ramp waveform).

The output voltage on startup is 0V, so the initial voltage across the inductor is equal to the input voltage. However, as the output voltage changes (and then reaches regulation) the above equation becomes

The peak inductor current is sensed by a small series resistor, R4, and when the voltage across this resistor equals a certain value (see the specific converter’s datasheet) the IC switches off the top MOSFET.

Now, inductors do not like having their current interrupted, so when the top MOSFET switches off, the inductor behaves like a battery to try to maintain the current flow. Referring to Figure 1, the output side of the inductor tries to fly positive (to push current out of the right hand side of the inductor) and its switched side (the left hand side) flies negative (to try and sink current into its left hand side) – in an effort to maintain the left to right current flow. Since the output side of the inductor is clamped by a capacitor, the left hand side flies negative. At this point the IC switches on the bottom MOSFET, Q2, to clamp the left hand side of the inductor to ground and enable the inductor to maintain its current flow.

Thus a current flows up MOSFET Q2, from left to right through the inductor and down into the output capacitor, thus charging the output capacitor.

When MOSFET Q2 switches on, it also provides a short circuit to 0V at the bottom of capacitor C6. Since the top of C6 is connected to the LTC3891’s internal linear regulator (INTVCC) via diode D1, this capacitor charges to INTVCC – 0.3V. The voltage on this capacitor is then used to provide a voltage higher than the input voltage to enable the top MOSFET to be switched on. Indeed, at startup, Q2 actually switches on before Q1 to charge the flying capacitor, C6, to enable Q1 to be switched on.

The process then starts again, with Q1 switching back on again and recharging the inductor.

The discharge cycle of the inductor is governed by the same equation as the charge cycle:

where V is the voltage across the inductor and is equal to the output voltage (since the left hand side of the inductor is clamped to 0V by MOSFET Q2)

The LTspice model of Figure 1 can be downloaded here (right click over the link and save as a '.asc' file): LTC3854 buck converter.

The datasheet of the LTC3854 can be downloaded here: LTC3854 datasheet.

Considering Figure 1, the input voltage is 12V, the output voltage (in regulation) is 5V and the inductor value is 6uH

Thus from

we can determine that change in current when the inductor is charging is

or 1,166,666 Amps per second.

When the inductor is discharging (when Q2 is on), the inductor discharges according to the equation

or

which equates to 833,333 Amps per second.

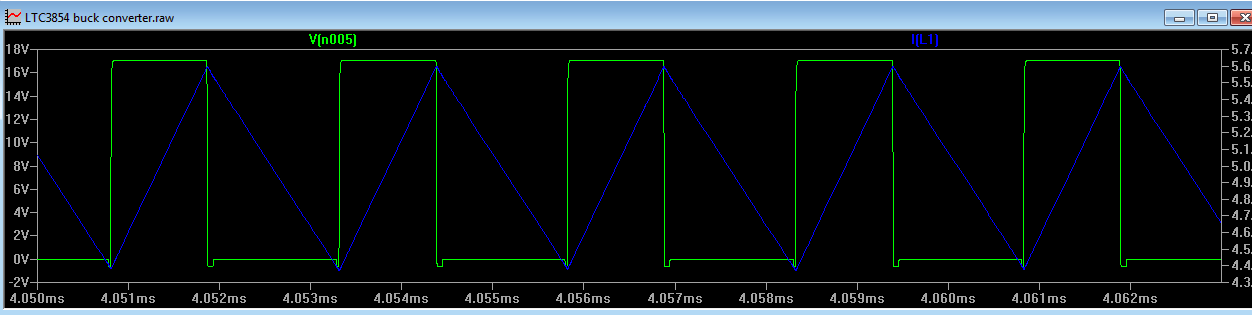

Figure 2

Figure 2 shows an LTspice simulation with the current ramping from 4.378A to 5.604A over 1.08us, a change of 1,135,185 Amps per second – not too far off what was calculated above.

During discharge, the current ramps down from 5.604A to 4.378A, but over 1.438us, a change of 852,573A – close to what we calculated. The discrepancy in the above is because each MOSFET does not present a perfect short circuit and actually has about 50mV across it when fully activated.

It is interesting to note that the value of di/dt is determined ONLY by the inductance value and the voltage across the inductor. The controller IC has nothing to do with setting the inductor ramp current.

It is also useful to calculate the duty cycle of the converter. The duty cycle is the ratio of the ON time of the top MOSFET to the total period of oscillation.

The inductor charges according to

During discharge, the current ramps down from 5.604A to 4.378A, but over 1.438us, a change of 852,573A – close to what we calculated. The discrepancy in the above is because each MOSFET does not present a perfect short circuit and actually has about 50mV across it when fully activated.

It is interesting to note that the value of di/dt is determined ONLY by the inductance value and the voltage across the inductor. The controller IC has nothing to do with setting the inductor ramp current.

It is also useful to calculate the duty cycle of the converter. The duty cycle is the ratio of the ON time of the top MOSFET to the total period of oscillation.

The inductor charges according to

and discharges according to

(here dt1 is the ON time of the top MOSFET and dt2 is the ON time of the bottom MOSFET)

In steady state, as can be seen in Figure 2 the charge current is equal to the discharge current, so

From this we can see that

so

so

and if Duty Cycle (DC) is a ratio of dt1 to (dt1 +dt2) then

So the duty cycle is equal to the ratio of Vout to Vin.

Note that the duty cycle is purely dependent on the input and output voltages and has nothing to do with the controller IC or inductor value.

The above is true as long as the inductor current does not fall to zero. The converter is then said to be operating in continuous conduction mode (CCM). If the inductor current ramps down to zero, the converter is then in discontinuous conduction mode (DCM).

In CCM if the load current changes, the duty cycle of the converter and the amplitude of the ripple current remain the same. The circuit responds to a change in load current by changing the midpoint of the inductor current (its dc offset). Indeed it is also true that the average inductor current in a buck converter is equal to the load current.

In Figure 2 we can see that the midpoint of the inductor current is 5A and it can be seen from Figure 1 that our load is 1 Ohm, thus the load current is 5A. If the load resistance were increased to 2 Ohms, the ripple current and duty cycle would remain unchanged (in the steady state), but the dc offset current would fall to 2.5A.

Buck Converter Design Procedure

We are going to use the LTC3891 to design a buck converter that converts from 24V to 5V and can supply a load of 2A. The LTC3891 datasheet can be downloaded here: LTC3891 Datasheet

The outline schematic is shown in Figure 3

Figure 3

With a 24V input and a 5V output, the duty cycle of the converter is

The LTC3891 has a selectable fixed frequency operation. Tying the FREQ pin to INTVCC (see datasheet) sets the frequency to 535kHz, thus a switching period of 1.87us. Thus the ON time of the top MOSFET will be 21% of 1.87us, or 389ns. At this point it is wise to check that the converter has a minimum ON time of less than 389ns. The LTC3891 has a minimum ON time of 95ns, so we are well within spec.

If the input voltage is very close to the output voltage, the duty cycle will be very high. In this case, it is worth checking that the calculated duty cycle does not violate the maximum duty cycle spec of the part. In any dc/dc converter with a high side N channel MOSFET (Q1 in Figure 1), the bottom MOSFET must switch on to enable the flying capacitor (C6 in Figure 1) to refresh and it is this refresh cycle that determines the maximum duty cycle of the converter.

Inductor Choice

It is good design practice to keep the inductor ripple current (di) to about 40% of the output current, so with a 2A load this implies a ripple current of 800mA. Increasing the ripple current increases the switching losses and output ripple, but means we can use a smaller value and size of inductor. Decreasing the ripple current means the circuit will be less responsive to load transients.

The current ramp in the inductor during charging is represented by

We know Vin, Vout, dt1 and the inductor ripple, di, so can work out the optimum inductor value.

which implies and inductor value of 9.24uH. A 10uH inductor should be suitable.

We know that the average inductor current is equal to the output current, so our peak inductor current is equal to the output current plus half the ripple current. For a 2A load, the peak inductor current will be 2.4A.

We need to pick a 10uH inductor with a saturation current rating of at least 2.4A. If too much current flows in the inductor, the ferrite that the inductor is wound on saturates and the inductor loses its inductive properties causing the inductor value to fall. From the equation

if the inductor value falls, the current ramp increases causing the ferrite to further saturate, causing more current to flow… Therefore we must make sure that the inductor never saturates.

Using the Wurth Electronics Component Simulation Software, we can see the 10uH, 3.5A saturation current 74404064100 is a good fit:

Regarding the placement of Wurth inductors on the PCB, the 'dot' on the inductor package represents the start of the winding. Therefore it is advisable to connect the dot end of the inductor closest to the FETs as this is the end that will undergo the most dv/dt and hence generate the most interference. If the non-dot end is connected to the output voltage (at dc) and the windings closest to the output voltage are wound over the dot end, they will give a degree of shielding to the inner (switched) end of the inductor.

Rsense Calculation

The sense resistor (R4 in Figure 3) senses the inductor current. The trip threshold on the current sense comparator in the case of the LTC3891 is 50mV (if the ILIM pin is tied to INTVCC), so a current sense resistor of 16mOhms should ensure that the peak current never rises above 3.1A – high enough that our peak current demands can be met, but lower than the saturation current of the inductor.

MOSFET Choice - General

In nearly all applications the specification for the top MOSFET is different from that for the bottom MOSFET if maximum efficiency is to be achieved.

Both MOSFETs will be exposed to the input voltage at some point during the switching cycle, so both must have a drain-source breakdown voltage of at least Vin. In our design, the input voltage is 24V, so a MOSFET rated with a breakdown voltage of at least 30V should suffice.

The peak current will occur just as the top MOSFET switches off and the bottom MOSFET switches on and the same magnitude of current flows through both devices. Our current sense resistor sets the peak current to 3.1A, so any MOSFET with a peak current greater than 5A is suitable.

Looking at the block diagram of the LTC3891, we see that the drive circuitry for the bottom MOSFET is powered from INTVCC. The minimum voltage specification on this voltage is 4.85V, so our bottom MOSFET must have a gate turn on voltage of significantly less than 4.85V. However, the drive to the top MOSFET is powered from INTVCC – 0.3V (the voltage across the flying capacitor) so the turn on voltage of the top MOSFET needs to be significantly less than 4.55V. In either case, a logic level MOSFET, with a turn on voltage of 1V - 2V is suitable.

The above parameters represent the bare minimum characteristics of the MOSFETs. However, to get a good design, we must ensure that the losses in the MOSFETs are as low as possible.

MOSFET Choice – Switching and Conduction Losses

The MOSFETs present two losses in the circuit: switching losses and conduction losses.

The switching losses result from current flowing through the MOSFET at the same time that a voltage is across the MOSFET (so power is generated in the MOSFET), during the turn on and turn off times of the MOSFET. For a given gate drive coming out of the controller IC, the lower the Gate-Source capacitance of the MOSFET, the quicker the MOSFET will turn on. Thus the Qg specification of the MOSFET is important and should be as low as possible. The Qg of the MOSFET will also have an impact on the heat dissipation of the chip, especially if the input voltage to the chip is high.

Charge is dictated by the equation:

Charge (Q) = Current (I) x Time (s)

Since Frequency is the inverse of Time, we can write

So we can calculate the current needed to flow into the chip, just to charge the gate capacitance of the FETs. Since heat is the product of voltage and current, if the gate charge is high and/or the switching frequency is high, the heat dissipation in the chip will be high if the input voltage is high.

Once the MOSFET has switched on, the MOSFET presents a small dc resistance between its Drain and Source terminals. This is the MOSFETs ‘Drain Source ON resistance’ or RDSON. Again, this needs to be as low as possible.

Now, MOSFET manufacturers reduce the ON resistance of the MOSFET by constructing many parallel conduction paths between the Drain and Source. Thus, like connecting resistors in parallel, the ON resistance comes down with more parallel paths. However, in connecting Drain Source paths in parallel, a negative effect is that the Gate Source capacitance (Qg) is also connected in parallel, so a low ON resistance (and hence low conduction loss) sometimes implies a high gate source capacitance (hence high switching loss). Thus the MOSFET that is chosen should be a compromise between these two characteristics. In addition, high current MOSFETs tend to come in much larger packages, so meeting the ideals of low ON resistance and low Qg might violate a space requirement spec, so the selection process has to start over. Engineering, as ever, is a compromise.

Indeed looking at the selection tables of the MOSFET manufacturers, it is better to select a MOSFET with a low ON resistance (less than 10mOhms), then filter this selection to remove MOSFETs with a Qg of greater than 10nC, then select a MOSFET from this list, as long as the Gate turn on voltage, Vds and Id can be met. Starting by selecting MOSFETs with a Vds of between 20V and 30V might rule out some higher voltage FETs that are better suited to lower voltage designs. Failing that, download all the results to a spreadsheet and sort from there. I have never had much luck with the parametric searches on MOSFET websites.

Alternatively, download all the MOSFET characteristics into a spreadsheet, remove the ones that don't meet the VDS and ID requirements, then add a column called FOM (Figure of Merit). This column should contain the value RDSON x QG. Then sort by this column and pick the FET with the lowest FOM. This part will be the best compromise between RDSON and QG and ideal for the top MOSFET.

Just to further complicate matters, if the application has a high input voltage and a low output voltage, the duty cycle will be low. Therefore the ON resistance of the top FET will be less important since the top FET will only be on for a short period of time. The lower the duty cycle, the less important ON resistance becomes. I designed a 12V to 1V buck converter where I spent ages picking the top FET to balance Qg and RDSON, only to get an efficiency of 84%. Changing the top FET to a low Qg one regardless of RDSON (it was about 65mOhms) increased the efficiency to 94%.

MOSFET Choice – Top MOSFET

The Duty Cycle governs how long the top MOSFET switches on for during each period of the switching frequency. We have calculated that the duty cycle is dictated by the ratio of Vout to Vin (for a buck converter operating in continuous conduction mode). So it can be argued that if the input voltage is high and the output voltage is low (i.e. a low duty cycle), conduction losses in the top MOSFET are not important since the top MOSFET is only ON for a short amount of time. Therefore for low duty cycle circuits, a MOSFET with low Qg should be chosen, almost regardless of RDSON. Although there is no figure as to what constitutes a low duty cycle, any circuit with a duty cycle of less than about 15% warrants having its MOSFET optimised for low Qg with RDSON being largely unimportant.

That said, our duty cycle is 21%, so unfortunately we should strive to find a MOSFET with both low Qg and low ON resistance.

Luckily the suggested LTspice circuit for the LTC3891 comes with an extremely good top MOSFET, the Renesas RJK0305. This device has an RDSON of 6.7mOhms and a Qg of 8nC.

MOSFET Choice – Bottom MOSFET

When the top MOSFET switches off, the voltage at the left hand side of the inductor flies negative, thus the voltage across the bottom MOSFET is nearly zero when the bottom MOSFET switches on. Therefore the switching losses of the bottom MOSFET are negligible, so we do not have to worry about the Qg specification of the bottom MOSFET. Only the RDSON characteristic of the bottom MOSFET is important.

In fact, every MOSFET has a ‘body diode’. This is a diode inherent in the structure of the MOSFET and in an N channel FET, its anode is connected to the source and the cathode is connected to the Drain.

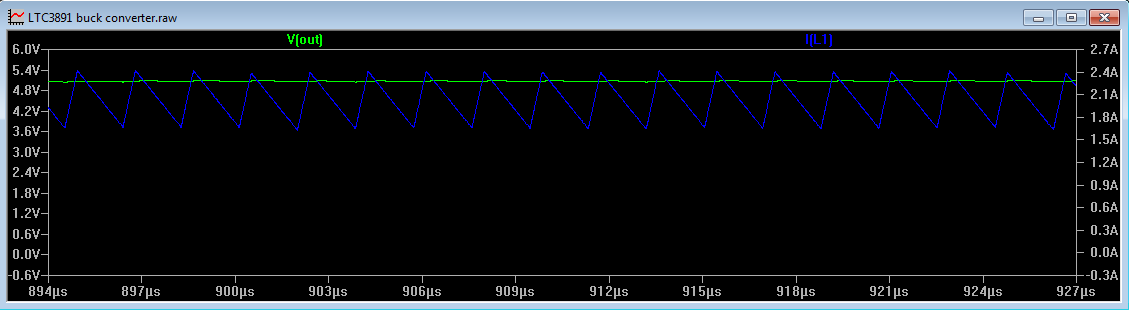

When the inductor voltage flies negative, it is the body diode that conducts first before the gate drive to the MOSFET activates the Drain-Source channel. Figure 4 shows a simulation of the switch node just as the bottom MOSFET is switching on.

Figure 4

We can see the switch node (V(sw)) falling to a voltage below zero well before the drive to the bottom MOSFET gate starts to rise. This is indicative of the body diode starting to conduct and indeed the negative voltage is approximately -0.6V. When the body diode conducts, it stores charge in the MOSFET that has to be removed before the MOSFET can fully turn on, so body diode conduction can affect the efficiency of the converter.

If optimum efficiency is desired, it is wise to place a Schottky diode across the bottom MOSFET, so the Schottky diode can conduct the inductor flyback voltage and not the body diode. The resulting increase in efficiency can be as much as 3%. The Schottky diode will conduct the peak current flowing through the inductor, but this current will only flow for a short period of time (until the bottom MOSFET switches on). Therefore, the current rating of the diode can be a lot less than peak inductor current. An MBRS340 has a reverse voltage rating of 40V, but a non repetitive peak forward current of 40A.

If optimum efficiency is desired, it is wise to place a Schottky diode across the bottom MOSFET, so the Schottky diode can conduct the inductor flyback voltage and not the body diode. The resulting increase in efficiency can be as much as 3%. The Schottky diode will conduct the peak current flowing through the inductor, but this current will only flow for a short period of time (until the bottom MOSFET switches on). Therefore, the current rating of the diode can be a lot less than peak inductor current. An MBRS340 has a reverse voltage rating of 40V, but a non repetitive peak forward current of 40A.

For the bottom MOSFET, the Renesas RJK0301 has 2.3mOhms RDSON and a Qg of 32nC.

Output Capacitor Choice

In continuous conduction mode, the capacitor has a continual current flowing into it from the inductor. Unlike a boost converter, the output capacitor in a buck regulator does not have to hold up the output while the inductor is being charged.

The output is made up of 2 components: the ripple current from the inductor producing a voltage across the effective series resistance (ESR) of the output capacitor and the ripple current charging the output capacitor according to the equation

Unlike a boost converter where the rectifier diode current jumps from 0A to the peak inductor current as the MOSFET switches off, the ripple in a buck architecture is determined by the ripple current amplitude, not the peak inductor current.

Recent innovations in ceramic capacitor design mean that very low ESR capacitors are available with high capacitance values. Ceramic capacitors have a typical ESR of 10mOhms. Failing that, low ESR tantalum capacitors are available in much higher capacitance values with ESRs of upwards of 50m Ohms. Of course capacitors can also be paralleled to increase the capacitance and reduce the ESR.

In our example the inductor ripple current is 800mA and the ESR of a typical tantalum capacitor is 70m Ohms, giving an ESR ripple of 56mV. Two such capacitors in parallel will yield an ESR ripple of 28mV.

To calculate the charging ripple, from the equation above we can see

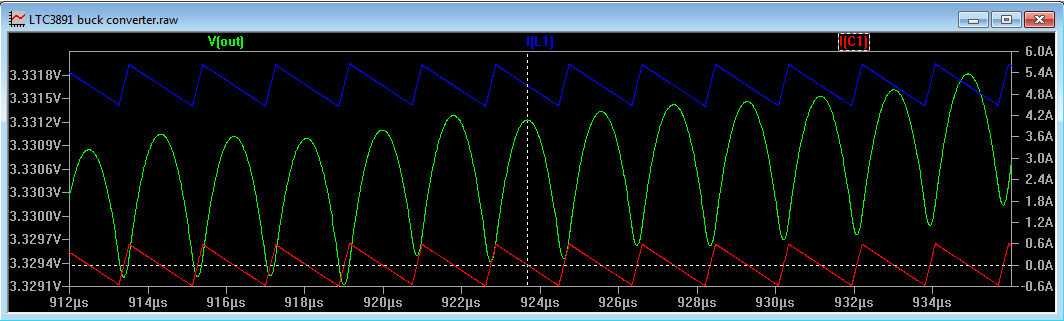

Figure 5

Figure 5, shows the inductor ripple current (in blue), output voltage ripple (in green) and output capacitor current (in red). For convenience, the output capacitor ESR has been reduced to 0 Ohms to illustrate the ripple due to capacitor discharge. It can be seen that the capacitor current has the same amplitude as the inductor ripple current, but does not have the dc offset current (of approx. 5A). This is easy to picture, since the output current is equal to the average inductor current (i.e. a straight line drawn through the middle of the inductor current) and any current that does not flow into the load must flow in and out of the capacitor. To obtain the capacitor current, just subtract the output current.

Now, we can see that while the capacitor current is positive (above the dotted white line) the output capacitor voltage goes up and while it is negative, the output capacitor voltage goes down. To work out the amplitude of the ripple voltage on the output capacitor, we must calculate the average of the positive part of the capacitor current (above the dotted white line). Since we know the peak to peak ripple current (is equal to the inductor ripple current), the peak ripple current is Iripple/2 and hence the average of this current (since half of the cycle is below zero) is Iripple/4. We can now work out the charging ripple.

From

Now, we can see that while the capacitor current is positive (above the dotted white line) the output capacitor voltage goes up and while it is negative, the output capacitor voltage goes down. To work out the amplitude of the ripple voltage on the output capacitor, we must calculate the average of the positive part of the capacitor current (above the dotted white line). Since we know the peak to peak ripple current (is equal to the inductor ripple current), the peak ripple current is Iripple/2 and hence the average of this current (since half of the cycle is below zero) is Iripple/4. We can now work out the charging ripple.

From

We can see that dt is equal to half the period, so we can say

Since our capacitor current is positive for half the ON time and half the OFF time, the above equation holds true regardless of duty cycle.

Let’s assume we want a total ripple voltage of 1% (50mV). We already have 28mV of ripple as a result of the capacitor ESR, so we now have a budget for the charging ripple of 22mV.

If our ripple current is 800mA and we are operating at a switching frequency of 535kHz, a capacitor of 8.5uF should suffice.

Our ESR ripple calculations assumed two capacitors in parallel to reduce the ESR, so two 4.7uF capacitors with an ESR of 70mOhms should ensure we meet our total ripple budget of 50mV.

Other Points

The feedback resistor values can be calculated using this spreadsheet:

A decoupling capacitor should also be placed on the input rail. The positive terminal of this capacitor should be situated physically close to the drain of the top MOSFET and the negative terminal close to the source of the bottom FET. When the MOSFETs switch, high changes in current occur at the input (probe the current into the drain of the top MOSFET to see this in LTspice). The input capacitor provides a local low impedance path for this current and helps improve EMC performance.

If the circuit is sensitive to fast current changes on the input (if a radio transmitter, say, is connected to the input rail), using a SEPIC converter in a buck only mode will give much quieter circuit operation.

The final LTspice circuit can be downloaded here (right click over the link and save as a '.asc' file):

Running the simulation, it can be seen that the ripple current is 750mA, the switching frequency is 536kHz, the ON time is 401ns and the duty cycle is 21.6% (all measured using the cursors in LTspice). This ties in closely with what we have designed for. The output ripple was also measured at 30.7mV. The ripple current and output voltage can be seen in Figure 6

Figure 6

LTspice is a registered trademark of Analog Devices Inc

Sitemap: www.simonbramble.co.uk/sitemap

© Copyright Simon Bramble